Our form of Homo sapiens, the anatomically modern version of “us,” appeared about 200,000 years ago. It would be preposterous to assume that in the chasm of time between then and now nobody had the wherewithal to dance, sing, or get together for a celebration. Indeed, no end of writers has found it mindlessly easy to conceptualize wild, orgiastic revels by our hairy, heavy-browed predecessors. But the evidence has been in short supply. That is until a fascinating discovery in 2006.

* * *

He crouches on his thin, brown haunches and nervously readies the poison by firelight. Even in the night’s chill, he sweats with concentration. His head fills with the vision of his brother writhing on the ground after a speck of the poison touched his lips from a careless hand wipe. Convulsions wracked him all of a night, with the morning bringing welcome death, his face grotesquely swollen and red. The same mistake will not be made this time.

In a small empty tortoise shell, the hunter carefully grinds the bodies of several reddish-brown beetles together with sticky tree gum. After slightly warming it over the fire, he gingerly applies minute amounts of the acrid mixture to a dozen bone arrow tips, taking care not to touch the poison to any opening in his body. As he finishes each arrow tip, he holds it up to the pale Sky Woman and chants his simple prayer for good fortune. He stores the arrow tips in hollow reed cylinders that will be fitted to his arrows just before the next day’s hunt.

Sleep in his hut comes fitfully, broken by the coughs and retching of three of his six children. His two wives vainly try to care for them. Reduced to miserable bundles of brown-skin covered skeletons and pleading eyes, they are dehydrated and nearing the final stages of starvation. A kill on the next day is crucial for their survival.

That day dawns like an obsidian blade, the sun’s first rays slicing clean through the freezing heart of the desert.

The hunter prepares. With two companions, he lays out the plan for the hunt. Their conversation is a wavering series of tongue clicks, melodic intonations, and limb gestures. Their final guide is a crude dirt drawing. As if toasting their agreement, they consume a hasty breakfast of locusts, berries, and minimal water, sustenance that must last most of the day.

The hunt does not go well. By mid-day, their methodical tracking has not found even the droppings of a single animal and the dry grasses and rough ground of the desolate Kalahari yield nothing but fatigue and sweat.

They pause.

Suddenly a jackal appears, scrawny and nervous behind a low bush. Does he wish death? The hunter pulls an arrow from his leather quiver and hits the mark, but the wound is shallow, the poison slow.

It is time to run.

The chase takes most of the afternoon. After his companions drop off as markers for the return trail, the hunter continues alone, pursuing the weakening jackal into poisoned exhaustion. He has been in a constant trot for four hours, his only refreshment a short drink from an ostrich egg half-full of murky grey water that was stashed along this well-known hunting trail. The jackal whimpers plaintively as the hunter completes his kill with a rock and pauses to stroke the dead animal’s forehead in a gesture of spiritual connection. With what is left of his ebbing strength, the hunter returns the long distance to his companions with the animal over his shoulders. Their smiles announce a shared pride in the achievement. It is a good day after all. Perhaps the Sky Woman has answered his prayer.

But the answer is a temporary one. Even with the women’s efficient rationing, the hunter knows that the jackal will only provide relief from approaching starvation for a short time. It must feed all the families, too many mouths for such a small animal. Without a kudu or eland kill, they will all die.

The hunter knows his place. He cannot force the band to move for game; he cannot rule their lives. Only the spirits do that. He knows it is the place of the shaman to visit the spirit world and bring back the herds of game that have always come in the past.

Two days after the jackal kill, with the setting sun warming their backs, the small band of men, women, and children slowly treks around the rocky outcroppings leading up a steep hill from the scraggly desert floor to the “Rock that Whispers.” They are all clad in their finest leather loincloths, and the women wear short skin cloaks over their shoulders and breasts. Everyone has one or two amulets of snail shells on their wrists or around their necks, gifts from the recent travelers from far away. The adults carry small leather bags slung over their shoulders. The men hold reed torches to fend off the cold of the gathering desert night and to help light their way. As they climb, they all chatter excitedly about the curing ceremony soon to unfold, their clicks and hums echoing off the surrounding rocks.

Slightly hidden away from the main path, the “Rock that Whispers” is a large cave, home to the Serpent. In the long ago, legend tells it was the Serpent that dug the riverbeds as it circled these hills searching for water. Its home is a sacred place. Approaching the dark rocks forming the cave entrance, two of the hunter’s still-healthy children begin crying. They are exhausted from the climb and from a daily diet of only a handful of locusts and nuts. Whimpering, they crouch down to enter the cave, followed by their mother. Inside, they join the other families seated on the floor of the large rocky chamber. The mother gives the children a few berries gathered on the long climb up the hill to help quiet them. The hunter finally sits down cross-legged beside them. He places his lit torch in line along the wall beside those of the other families. He looks worried. What has he done—what have they all done—to bring this famine on themselves? He and the others believe that they have somehow angered the Serpent, who has kept the animals away. They must appeal to the Serpent to right their wrong. He can only pray that tonight’s curing ceremony will bring the game back and save them in time.

The ceremony begins. One by one, the men add dry branches they have gathered to a growing fire in the middle of the chamber. As the fire builds, the fearsome Serpent comes alive in front of them, its stony eye scowling at each person. Its body slithers in the lambent firelight as if to seize them and carry them to the far-off place where it lives with the other animals. Into this terrifying world they must venture tonight to find the spirits of the game and bring them back to the desert. Their shaman will lead the way.

He sits alone under the head of the Serpent, waiting, his dark eyes closed. His thin face, pinched and nervous, is luridly painted. Black ash forehead, red ochre cheeks swiped as if with the blood of the kudu. Smears of ochre adorn the rest of his torso and limbs in bizarre slashes. Ankle and wrist bracelets of snail shells accompany a necklace of ostrich eggshell beads as adornments. A long kudu-skin cloak covers his body. It is topped by the animal’s terrifying death mask, complete with curled horns. This is the garish ensemble of a powerful spiritual leader. His mere presence instills fear and respect in the onlookers. They are at his mercy.

He motions to the adults who reach into their bags and remove two stones each, one a finally crafted spear point and the other a chopping stone. They are the stones brought by the travelers from afar. The band gave some of their precious meat to the strangers in exchange for beads and these sacred stones, especially the magic red spear points they had never seen before. Each person takes their chopping stone and makes a clean stroke on the side of the serpent, adding yet another reptilian scale. For a token sacrifice, they place the red spear points onto the blazing fire. The shaman throws powdery perfume onto the flames, which glitter and burst into showers of sparks.

As smoke fills the cave, the shaman sits peacefully several moments longer. Then…movement—slow, subdued. The hunter knows what is coming.

He watches as the shaman’s hands, resting on his crossed legs, begin to tremble. The face twitches, at first almost imperceptibly, then suddenly uncontrollably. His eyes remain partially closed, eyelids fluttering. Low guttural sounds issue from his mouth as he rises from the floor and beckons all to take part. The women and children begin to clap loudly and soon add mouth clicks and vocal intonations. The Serpent slithers even more wildly as the rhythm accelerates. The journey begins.

After the guttural grunts, more spirit voices pass through the shaman. As he twirls and reels in improvised dance, his eyes rolling back, the kudu and eland spirits arrive with snorts and snarls. The hunter and other men join him. They catch his mesmerizing ecstasy. Jumping … crouching … spinning … their bodies move almost uncontrollably in time with his. They are all in the spirit world now. Wild screams come from the shaman. Arms outspread, he is bent forward at the waist and spinning with abandon. His nose bleeds profusely and the hunter knows he must be communicating with the animal spirits. Shrill chanting pours from the women. Their hands beat a frenetic tempo. The cavern is a surreal expanse of two worlds, spirit and real, no longer separate. The muskiness of smoke, sweat, and leather permeates the air. As the night wears on, the dance ebbs and flows like the beat of a heart, some men resting while others take their places, the women and children continuing to clap and chant at an unwavering tempo. As the approaching dawn sends shafts of light through the cave, the men all join in again, this time dancing faster as the women sing louder and increase the rhythm. The shaman, by now nearing complete exhaustion, soon utters a final scream and deathly groan, collapsing into a state of mystical fatigue on the dirt floor. The leather cloak and kudu horns fall loosely like a dead animal over his panting body. The men stop their trance dance and sit exhausted nearby. Hands and bodies are stilled once again. Save for heavy breathing, all is silence. At that moment, a voice, faintly audible, seems to come from within the Serpent. “I am happy. Go. Hunt.”

They have returned from the other side. Life will go on.

* * *

This story is a fictional reproduction of what might have been one of the world’s oldest special events. Unfortunately, “might have been” is the only way we can surmise how the lives of our ancestors unfolded in prehistoric times. Educated guesses take the place of recorded history for the period between the first appearance of bipedalism in our very distant relatives, the Australopithecines more than 3.5 million years ago, and the modest beginnings of true civilizations with written records, about 5,500 years ago in the near east. This is one of those guesses.

Fortunately, archaeological evidence helps to explain what took place during this period. The above account is based on just such evidence. In 2006, in the remote Tsodilo Hills of northwestern Botswana above the Kalahari Desert, archaeologists uncovered ritual objects in a hidden cavern known as Rhino Cave. These objects included a rock resembling the head of a huge python. Along with this, they dug up over 13,000 stone spearheads and tools, some more than 70,000 years old, the time of the Middle Stone Age.

Location of Tsodilo Hills in Botswana

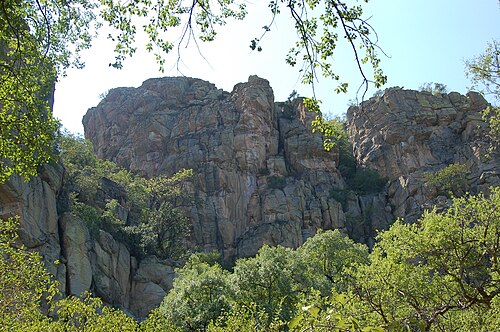

Tsodilo Hills (Photo courtesy Joachim Huber via Wikimedia Commons)

Associate Professor Sheila Coulson of the University of Norway made the discoveries. She speculated that the cave was an important one for ancient rituals. “You could see the mouth and eyes of the snake. It looked like a real python. The play of sunlight over the indentations gave them the appearance of snakeskin. At night, the firelight gave one the feeling that the snake was actually moving.” She also discovered a secret chamber behind the python stone. Some areas of the entrance to this small chamber were worn smooth, indicating that many people had passed through it over the years. According to her, “The shaman, who is still a very important person in San culture (the famous ‘Kalahari Bushmen’ indigenous to the area, and from whom we are all descended ), could have kept himself hidden in that secret chamber. He would have had a good view of the inside of the cave while remaining hidden himself. When he spoke from his hiding place, it could have seemed as if the voice came from the snake itself. The shaman would have been able to control everything.”

The sacred python stone during the day (above) and at night (below), as it may have been during worshipping. (Photos courtesy Dr. Sheila Coulson, Institute of Archaeology, Conservation and History at

University of Oslo)

University of Oslo)

If Dr. Coulson is correct, then this is convincing evidence for one of the world’s oldest rituals. For the small band who participated, it was more than ritual, it was a true "special event." Perhaps in coming years more such exciting discoveries will be made of even older celebrations.References:

- Boswell, Randy. (Dec.1, 2006). Rock carving of snake hailed as world’s oldest religious relic. The Vancouver Sun. p. A1.

- Stix, G. (2008). Traces of a Distant Past. Scientific American, July. pp. 56-63.

- Vogt, Y., Belardinelli, A.L., and afrol News staff (1 December, 2006). World’s oldest religion discovered in Botswana. afrol News. Retrieved April 8, 2008, from http://www.afrol.com/articles/23093.

No comments:

Post a Comment